Aspiring professionals looking for a competitive edge should tread carefully, writes Olivia Stewart.

Dance competitions are far from new, but their more recent ability to launch careers through television reality shows, film documentaries and social media has multitudes jumping on the bandwagon.

The world of professional classical ballet, with its predominantly company-based structure, is somewhat impervious to the impact of such phenomena. But, with the Youth America Grand Prix – documented in the award-winning 2011 feature First Position – coming to Australia for the first time in 2019, it’s opportune to examine the real benefit of such competitions, especially for those who might be thinking they present a short-cut or guarantee to a professional career in ballet.

Certainly First Position’s six featured contestants had the eyes of the world on them after the film’s release. Five of them went on as expected to join professional ballet companies: Miko Fogarty, Aran Bell, Michaela DePrince, Joann Sebastian Zamora and Rebecca Houseknecht.

Fogarty entered Birmingham Royal Ballet’s corps at 18 in 2015, after claiming several prestigious international ballet competition medals, including gold at Moscow in 2013 and silver at Varna in 2014.

But it became apparent that the dream was not as it seemed when Fogarty left Birmingham after just a year, and disappeared from the radar.

It was only in August 2018 that the 21-year-old re-emerged publicly, in a part-time teaching/coaching role as conservatory director of the newly-established San Jose Dance International, and finally announced she’d retired from dancing to attend university. She’s studying biology as a precursor to medicine.

While her shooting star trajectory made Fogarty’s decision a shock to many, Rebecca Houseknecht had earlier also bowed out from professional ballet aged 19 in favour of studying, leaving Washington Ballet to train as a speech pathologist. After going public, Fogarty realised sharing her experience could benefit others.

Speaking to Dance Australia via FaceTime, Fogarty reveals that she was having doubts about ballet as a career long before joining Birmingham. By then she had been dancing for 14 years, for the last six training 30 hours a week and home- schooling, with social media, photo shoots and regular travel on top.

“It did definitely feel like a full-time job previously, so I’d already been doing this career for a while, and accomplished so many of the things I wanted to,” she says. “I’d performed all over the world in the biggest galas and on the biggest stages and done different soloist (and) principal roles already.”

Despite her gratitude for these opportunities and rewards, eventually Fogarty couldn’t ignore the fact she was unhappy.

She was supposed to be living her dream, but she was experiencing anxiety over performing and had developed eating issues from struggling to maintain the ideal ballerina physique after puberty. She was also feeling unfulfilled.

Initially, her nerves had made her dance better in competitions but over time the sense of apprehension negated her enjoyment. “I don’t really want to be feeling like that all the time,” she explains. “It just wasn’t worth it for me to keep going.”

Fogarty’s experience highlights that there are many factors that will determine whether being a professional dancer is the right career fit, more than any child or their parent might first contemplate – especially with ballet, where body shape can cruelly undermine other attributes.

The director of First Position is Bess Kargman. She is well-placed to advise that there are pros and cons to consider when taking the competition route, with some students benefitting more than others. The main advantages of competitions are the learning opportunities and stage experience they can provide.

“Obviously the most positive thing is that if you’re a nobody – you have no connections, your parents weren’t dancers, maybe you do or don’t get trained at a top school – you can be seen, and you could potentially earn a scholarship,” Kargman says, adding that this can be life-changing.

Sometimes scholarships might be offered privately, and older competitors might receive employment contracts. So on this basis, these types of competitions can be worthwhile.

Along the way, the child is gaining performance experience, when other opportunities might otherwise be infrequent. “It gave me a lot of stage experience and by time I was 15 or 16 I knew how to get myself ready to perform and not make too many mistakes on stage, which was really great,” Fogarty affirms.

The opportunity to taste what it might feel like to be a professional dancer can also be something to savour for those who don’t ultimately achieve that, Kargman believes. On the other hand, there are unhappy children participating who exemplify that competitions aren’t for everyone.

“There’s a whole section of kids coming up who have to decide, like have a real talk with themselves, about whether or not competing is right for them,” Kargman counsels. “If they miss that moment of being onstage and performing for an audience because they rarely get to do it in their dance school, competing could be a wonderful outlet for them. “But if they never crave performing and being under the spotlight, and being potentially nervous and having to intensely prepare for months, then (it) isn’t for them.”

Even if it isn’t immediately apparent, as occurred in Fogarty’s case, the pressure that comes with performing in a competitive environment versus the informality of a dance school’s annual concert can sometimes override the benefits.

“When I was really young I did enjoy performing, but competitions were starting to be what made me get nervous,” she acknowledges. “Especially the older I got, the more pressure there was for me and the more I got nervous. The really big competitions (were) very nerve racking.”

Cautions Kargman: “Even when a dancer acts so mature, so poised, so driven, so determined – like pre-professional – we have to always remember that they’re children, that they don’t always know what’s best for them.”

Parents and teachers should “look for moments when they need a break, or when they’re delving into less healthy behaviours, and steer them away from pushing themselves too hard or having anyone else push them too hard”.

“I think with a lot of these kids, the engine, as with Miko, comes from within, but sometimes you don’t realise you’re overdoing it until you look back on it.”

In the quest to acquire advanced skills prematurely, or present in a particular way, ambitious kids can also develop patterns that will need to be corrected.

Fogarty acknowledges that she picked up bad habits. “Because I’d started searching for additional skills too early, I learned them in a bad way,” she reflects, “where taking that a little bit slower would have been good.”

Pre-professional instructors are known to view less as more in this respect: “Companies with academies often spend time reshaping children who may have learned a style or habit that isn’t desirable,” observes leading dance educator and former Australian Ballet principal artist Janet Karin, who herself only began studying ballet aged fourteen.

Karin taught privately then at the Australian Ballet School from 2001 to 2016, and is currently a professional associate at the University of Canberra. Her parallel involvement with dance medicine provides an invaluable holistic overview and insight.

When putting competitions in perspective, perhaps the most critical factor to ponder is their fundamental quantifying nature, when art is about expression. In addition to increasing risk of injury and burnout, training focused on external rewards is less likely to produce enduring satisfaction, Karin warns.

“Reaching for the highest goal – that always worries me a lot and you often get that when kids are starting ballet,” she says. “Explicit goals are external criteria and you know whether you’ve reached them when you get a good mark in the exam or praise or applause or a cup or whatever.

“With implicit learning, your feedback comes from that knowledge, or the amount of satisfaction it gives you as a physical and emotional and aesthetic experience, not what somebody else tells you or whether you’re getting the top mark and getting the best roles.”

This assessment supports the view that working on short showy solos for competitions isn’t useful preparation for the actual day-to-day reality of company life, which can be much more mundane.

“That’s a shock to the system for a lot of them,” Karin confirms. “If you’re aiming all the time for that extrinsic, explicit feedback, you get into the corps de ballet or you start dancing professionally and the gilt falls off. Unless you find your reward in the actual experience of dancing, it’s not exciting.”

The vast majority of those who enter companies do not arrive as competition darlings or child prodigies, so it can be misguided to think that these credentials will land you higher or fast-track your ascent. You’re assessed on what you do now, for a particular institution – be it your progression through a training course, or a company audition or class, or the roles you’re cast in once you’re hired – and there is no shortcut to hard work.

Karin relates an anecdote illustrating how an identity as a champion can create false expectations that prove counter-productive.

“When they do a lot of competitions, they’ve been so used to just waiting for the good feedback. I know somebody who some years ago got into our ballet company; they had a lot of talent and in their school they were regarded very highly.

“When they got into the company they basically just floated around looking boring as can be and nothing happened. Finally, I said to her, ‘How are you going?’ and this person said, ‘Oh, well I’ve been waiting for them to give me something so I can get my teeth into it.’ I said, ‘Do you think if you got your teeth into your dancing first, it might make a difference?’”

Maybe the penny dropped: “Later, she got something really good, and she couldn’t wait to tell me that at last they’d recognised her great talent which she hadn’t bothered to show anybody,” Karin laughs.

“That really amuses me but it also makes me feel very sad – it becomes a funny sort of contract, like you owe me before I’ll produce it.

“Whereas if they’re all the time exploring, and feeling new things going on through merging their minds and their bodies and the sensations that they’re getting and the artistic feedback, the emotional results that they’re getting, that’s never ending,” she chuckles. “You can dance till you’re 100 and still be exploring that.”

There’s no doubt that in our age of instant gratification and Insta-fame the lure is greater than it’s ever been for aspiring performers to put themselves on the biggest stages possible.

Perhaps the best protection is to always check in with your inner joy from dancing, which needs no audience, and to make sure it’s still there when there is one.

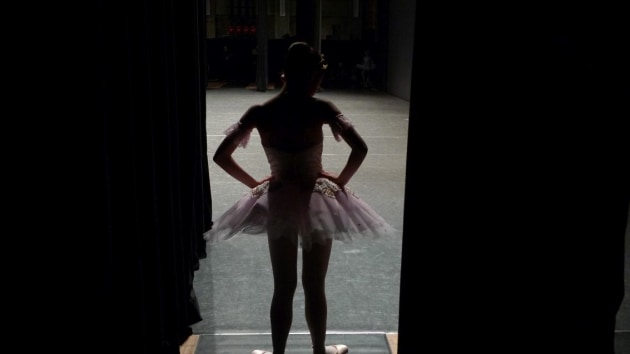

Pictured top is First Position director Bess Kargman with Miko Fogarty, at the time of making the film.

This article appears in the December/January issue of Dance Australia... OUT NOW! For more articles like this one, buy Dance Australia from your favourite retailer, purchase an online copy via the Dance Australia app or subscribe here.