A big book of Bolshoi buzz

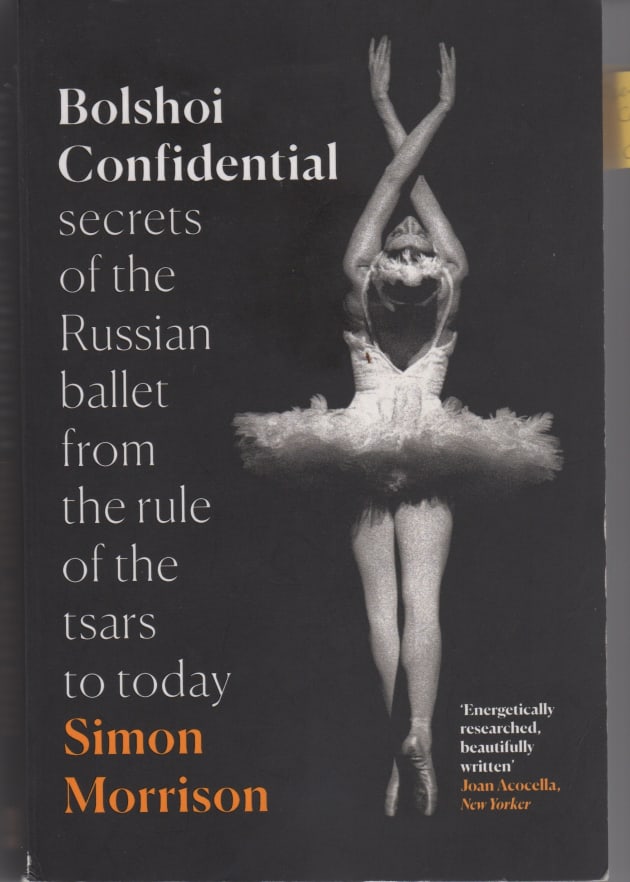

BOLSHOI CONFIDENTIAL

– secrets of the Russian ballet from the rule of the Tsars to today

By Simon Morrison

RRP $34.99 paperback

In 2013, the artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, Sergey Filin, was blinded when a company dancer threw acid in his face. The spiteful barbarism of the attack made headlines throughout the world. The author of this book, Simon Morrison, uses it as the springboard for this 500 page examination that promises to be both a serious and salacious history.

Morrison gained exclusive access to state archives and private sources to write this book, and it is thorough to the point of tedium. He begins with the company’s establishment as the Petrovsky Theatre in 1776 by Englishman Michael Maddox. The building burnt down in 1805. Following the Napoleon invasion, the theatre was rebuilt in 1825 in its now more familiar incarnation as a symbol of Russian identity. It was rebuilt again in 1856, opening with Italian ballerina, Fanny Cerrito, as a guest artist.

Under the Tsars, the Bolshoi went through various changes of leadership, and the repertoire and reputation grew, particularly with the arrival of Petipa. We are told he was a ‘tomcat’ and a plagiarist. The creation of his Don Quixote is described, as are the many revisions of Swan Lake.

Morrison delights in the affairs, vanities and scandals of the ballerinas, such as Sobeseshchanskaya (who was not taken with Tchaikovsky’s score for Swan Lake). He also details the life Matilda Kshesinskaya (b. 1872), the mistress (for three years) of Tsar Nicholas II, who released chickens on to the stage of her rival, and Ekaterina Geltser (b.1876), who was an “icon of Soviet artistic power”.

The real scandal, of course, was the treatment of the artists under the Soviets, particularly Stalin. Morrison is a musicologist and his account of this period focuses largely on the ordeals of composers such as Prokofiev and Shostakovich, as well as the choreographer, Lavrosky. He devotes a whole chapter to the ballerina Maya Plisetskaya (b. 1925), drawing on her published memoir. (The contented Ulanova gets less mention.) Artistic director and choreographer Grigorovich also features, of course, and detailed accounts of his creation of the ballets Spartacus and The Stone Flower.

But it is with Plisetskaya that Morrison’s account largely comes to an end. While the subtitle of his book claims to be about Russian ballet "to today", his coverage of modern times is relegated to the epilogue, and concentrates on one ex-pat choreographer - Alexei Ratmansky. For a book of such purported scale, this is a strange lack. We learn nothing, for instance, of the reaction to departures to the West of celebrated dancers such as Alexander Godunov, who defected in 1979 and caused a diplomatic incident, Erik Mukhamedov (who joined the Royal Ballet in 1990) or Natalia Osipova, who left for “artistic reasons” and is now with the Royal Ballet.

For the most part, the book is overstuffed with detail – from technicalities about the building to minor officials – yet the real Bolshoi – the school, students, dancers, teachers – remains opaque. Because Morrison focuses on grievances, grudges, conflicts and personality flaws, rather than successes and achievements, his account takes on a rather catty, jaundiced tone. Like many American writers, Morrison’s view of dance culture outside the Anglo world is limited. You would never know from this book, for instance, that the Bolshoi was lauded and envied in the West for its sensational technique and the prowess and masculinity of the male dancing. You would not know that Lavrosky’s Romeo and Juliet so astonished UK choreographers MacMillan and Cranko that it inspired their now classic versions fo the same ballet.

Bolshoi Confidential is jam-packed with information that is often interesting but often distracting and banal. A book on ballet is always welcome, and but this one is not even-handed or definitive.

– KAREN VAN ULZEN